The Farm Bill’s Impact on Land Prices

By Eric Fuchs, Understanding Ag, LLC.

I often wonder what the true value of farmland is in the U.S. I hear instances where Iowa or Illinois dry-land farm ground is going for $20K-plus an acre, and I wonder how that pencils out? I saw instances where pastureland in South Dakota was renting for $100 an acre. Even with $4-bushel corn and $12-bushel beans, it is hard for me to see how that works economically. I often wonder if they are using some “magic” pencil to come up with a value.

And it begs the big question: How is land priced these days? Is it priced for what it will produce as a crop? Is it priced for its value as an appreciable investment? Is it priced for the number of big bucks or covey of birds one might be able to flush off the acres? What is the main driver of land prices? Who is purchasing this land?

Let’s take a quick look at how one unseen factor—U.S. farm policy—affects the price of agricultural land.

Thanks to the Farm Bill’s Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), rental rates are guaranteed income for many producers. When a producer can buy land and enroll it in CRP, this is a guaranteed revenue stream for at least 15 years and recently, rental rates for CRP were increased. Due to weather challenges of the past several years, this land has been made available for grazing or haying, adding to the value gained by the producer/owner.

This guaranteed return further drives up the price of land. Crop insurance is another program which manipulates land prices. (UA consultant Doug Peterson, wrote an insightful article on crop insurance that I would suggest you read.)

Any guaranteed return and investment will drive land prices higher for investors, which in turn, drives the prices higher for producers wanting to expand their operations—or for new and beginning farmers trying to acquire land.

We are not talking about magic pencils here. Land is priced according to a number of return-on-investment factors, not just on the price of corn, beans or beef or its ability to produce agricultural products.

Much of this land is being managed by people who don’t own it, which can create longer-term stewardship conflicts and begs the question: Does a renter care for land as good as an owner?

How does this affect the new or beginning farmers who might want to buy a farm or ranch or to buy into the family operation? How does someone brand new to the game, and with less accrued capital, compete with those who are already playing or have land purchased before the inflated prices came to be?

What would land prices be without these farm programs? Would investors still be interested or would land be priced according to the true production value of the crop or livestock it produced?

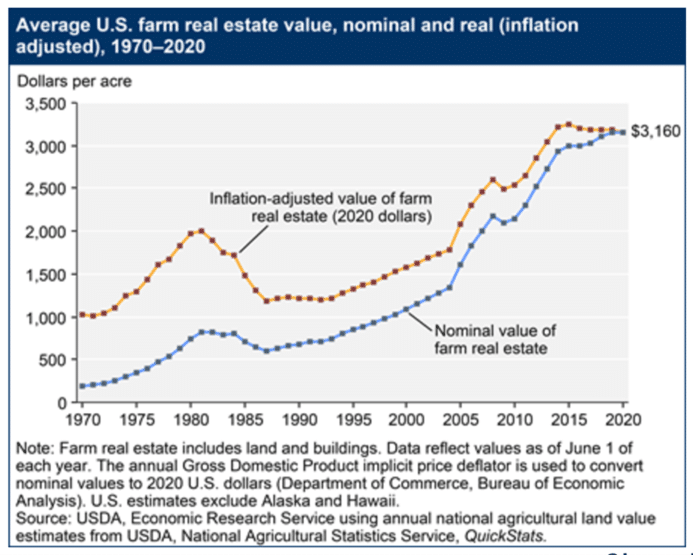

According to a report issued by USDA’s Economic Research Service, adjusted for inflation, U.S. farm real estate value has more than tripled since 1970. No doubt, several economic and investment factors are contributing to this alarming trend, but U.S. farm policy has certainly provided an accelerant to the farmland real estate boom. The consequences resulting from that on-going policy are significant and pose a long-term threat to the future of our family farms and rural communities.

My next post will examine how the size of agricultural operations also impacts rural communities and their economies.