When many people think of cover crops on their farms, their initial thoughts circle around soil erosion, either via wind or rain. Many of the programs through the NRCS and Soil and Water Conservation Districts that have anything to do with cover crops pertain to erosion problems as well. But those who have been using cover crops for a few years start to use different language such as soil health, bacteria, protozoa, mycorrhizal fungi. Ok, ok, maybe not everyone is using this language, but a growing number of people are talking about soil health even if they are not sure what it is.

It seems today that “soil health” has become a rather generic term. Soil health to some can be purchased in a jug—as in a “bug-in-a-jug”. I imagine the pitch for these products going something like this: “Step right up folks, check out this magnificent jug that has five microbes that your soils need to function. All you need is five of them and apply it as a seed treatment, as an in-furrow application, as a foliar feed! This will solve all your problems and only cost you $15.99 per application! But wait there’s more! Purchase today and we will throw in this nice ballcap and a pair of gloves.”

Ironically, many of these products have humic acid as the carrier. Any crop response seen is likely due to the humic acid. Some of these products will work on conventional ground but when applied to soils that have had the focus of the principles of soil health applied to them, they generally do not have any response other than a waste of money. Most of these products have at most maybe 5x108 cfu/mL of each microbe claimed to be in the product. If this was to be calculated out as, let’s say a seed treatment where 8 ounces of the product was to be mixed per 100 pounds of seed, this could mean that you’re effectively placing maybe 100 actual microbes per acre in the soil. Let’s think about this. The soil on a per-acre basis contains roughly:

• 800,000,000,000,000,000,000 Bacteria

• 20,000,000,000,000,000 Actinobacteria

• 200,000,000,000,000 Fungi

• 4,000,000,000 Algae

• 2,000,000,000,000 Protozoa

• 80,000,000 Nematodes

• 40,0000 Earthworms

• 8,160,000 Insects/arthropods

*Soil Food Web

Can it be expected that 100 added species of microbes applied as a seed treatment are going to do anything with all these other critters in the soil already? And how do we know if the bacteria in the jug are the right bacteria for our soils or even if the bacteria that is claimed to be in the jug are in the jug or if they are even alive still? There are about 5,000,000 known species of fungi, of which there are 250 known species of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. How do we know if the fungi that is claimed to be in the jug is the right one for your crop or soils? The fact is we don’t.

This is why we focus on principles and not products, at Understanding Ag.

Some believe that soil health pertains to the chemical makeup of the soil. This past year, I have noticed a lot of new tools and gadgets that have been brought to market, promoted as a new soil health tool, but they only look at the chemical aspect of the soils. Which makes me question what metrics were these tools calibrated to? Many do not believe the Haney test is a good method of measuring soil nutrients because it is not “calibrated.” Ironically, the Haney test uses extracts that mimic what the natural system would see as mild acids from root exudates and, get this, water! So, if these new, in-field tools are calibrated to the standard soil test using harsh acids that nature never sees and taking pH out of the equation—coupled with the fact that farming practices today are drastically different than farming practices of the 1950’s when these soil testing methods were developed—are these tests even reliable or effective for farming today?

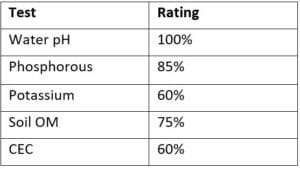

According to the Illinois Agronomy Handbook C1394, the usefulness and cost effectiveness of soil test are as follows:

All of these input decisions that are made off of a soil test that have this kind of reliability makes me question what have we been spending our money on for all of these years? Are we measuring the right things? Are we asking the right questions? It’s no wonder that every summer there are blue-green algal blooms in waters across the country and that we have a massive dead zone (hypoxia) in the Gulf of Mexico.

The NRCS defines soil health as a “continued capacity of the soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals, and humans.” At Understanding Ag, we focus on soil health through principles, rules and processes that drive the system: The understanding of the 6 Principles of Soil Health, the 3 Rules of Adaptive Stewardship, and how these together work to drive the 4 Ecosystem Processes (the 6-3-4TM). No matter where a person lives, what their annual rainfall amount is, or how long their growing season is, the 6-3-4TM remains the same. If the sun shines on your farm, these principles, rules and processes will work on any farm. Practices will change depending on a farm’s environment and other context-related factors. Products are manufactured for sales, and while they may have good intentions, they are designed to make money from the person purchasing them. This is why we do not sell or recommend any products at Understanding Ag.

In a recent podcast, Doug Peterson mentioned that if he could measure one soil indicator to determine soil health, he would look at stable soil aggregates. What does this mean? Aggregates are formed through microbial associations between plant roots, decaying residues, and the particles of sand silt and clay that are glued together from microbial secretions. Macro aggregates are formed via fungi, while the tiniest micro-aggregates are formed by bacteria. The stable aggregate remains constant during wet periods and dry periods, as long as the principles are in place. Although aggregates may only last up to three weeks before they are consumed, this building and rebuilding process will ensure that the soils can properly infiltrate water, cycle nutrients—including oxygen into the soil and carbon dioxide out of the soil—and it ensures that the system is not “leaky,” meaning that nutrients are stable as well and do not leach through the soil profile.

A simple tool that every farmer should carry in their truck to examine their soil aggregate structure is a spade. This inexpensive tool can help farmers to become more observational. Use it to compare cropland acres versus a near by fence row or even road ditch with grasses and other broadleaves growing and ask, Do the soils look the same? Which soil has more of a “cottage cheese” appearance? Do the soils smell the same? Which spade full of soil feels heavier than the other? As we ask ourselves these questions, we need to also ask ourselves the most common question of a toddler “Why?” We need to ask this question for everything until we have reduced our understanding of why something is what it is to its most basic level and to a point where the question can no longer be answered.

Ok, so this is all good and well. We plant cover crops and that reduces erosion, and they also build aggregates, right? Well, kind of. The rest of the story comes from the management of the cover crop including the application of nutrients; when to apply, what to apply; how much to apply. We also need to ask, “How much soil microbial activity does the field have? What’s the next cash crop? How does managing carbon to nitrogen (C:N) ratios of cover crops effect principles, and also the nutrient cycling of the soil? How do we capture and store every drop of rain that falls on the field for future use?”

Is it starting to feel a little bit complex and complicated? There are a lot of moving pieces of the puzzle when farming in a regenerative manner that requires a lot of planning and plans for plans when those plans are no longer a viable option for whatever reason. This is why I always tell farmers that when they go down the regenerative journey they will often have to use two sides of their brains. One side to tell them to be patient and the other side to tell them to be flexible. There are many signals that must be read by what the entire system is telling us before we make any actions.

But then, some things happen that are as much out of our control as Mother Nature’s mood swings. In the fall of 2021, China announced the ban of all phosphate exports. Throughout the winter of 2021 and into 2022 the price of nitrogen climbed steadily higher. Sulfur products are becoming increasingly difficult to contract. Some herbicides have taken as much as a 300% price increase since 2021. In some instances, retailers are telling their sales staff to not even mention certain products anymore because there is no supply. As I write this, last night Russia invaded Ukraine. What might that do to the cost of fuel and other inputs? Across the corn belt, there is a growing concern among corn farmers about the need to spray fungicide either later in the reproduction cycle or twice due to the spread of Tar Spot.

I would challenge folks to start thinking differently about farming. We need to start thinking about ways to reduce the need for synthetics. Notice I did not say eliminate them. This is the difference between organic and a regenerative approach. Organic removes all the tools in the toolbox whereas regenerative still allows the use of the tools as needed. The right tool for the right job, if you will.

In the second part of this series, we’ll examine additional ways to become more observational and intentional in our regenerative farming journeys—and how these important management tools can affect our crops, our land’s resiliency and our bottom lines.