Kenansville, NC

Adam and Brandy Grady represent the 10th generation to live on the land that comprises Dark Branch Farms near Kenansville, NC. Located in the eastern coastal plains of North Carolina in Duplin County, the farm has been in the family since the late 1700’s. No one in the present generations remembers the exact year the family settled on the land, but 10 generations of succession is very impressive. There are very few farm families left in the U.S. that can make such a claim.

There are two families actively involved in the farm today. Adam and his wife Brandy, along with their children Caden and Anna Kaye, and Adam’s father, Clegg Grady. Adam and Clegg are 50% partners in Dark Branch Farms.

Dark Branch Farms is comprised of about 1200 acres of arable land, along with additional acreage in woodland. Situated in the coastal plains, the soil types are predominantly sandy and sandy loam. The farm is located about an hour and a half southeast of Raleigh, NC.

The family intends for the 11th generation to take over operations of the family farm and continue the long tradition. Caden has already taken a strong interest in the farm and his sister, Anna Kaye, enjoys it as well.

Transition Process

The Early Years

The story of Dark Branch Farms begins in the late 1700’s when farming was more of a subsistence model. Just feeding your own family was of utmost importance and anything left to sell to others was, as they say in North Carolina, “gravy.” Sometime in the early 1800’s, as the farm transitioned from purely subsistence to an actual business, tobacco was the major crop in the region. On Dark Branch Farms, tobacco crops were produced every year from the early 1800’s until 2015—a 200-plus year period of continuous tobacco production as a commercial crop.

Other crops were produced as well, such as small grains and livestock. For generations (Adam does not remember how far back) the family raised hogs and sold excess fat pigs to neighbors. In the Carolinas, hog-slaughter time was always in the fall of the year and most farm families would do their own slaughtering and butchering.

Adam’s Lifetime

Adam remembers his father starting some no-till practices in the mid 1980’s. Clegg decided that no-till was a way to effectively use smaller, less expensive tractors and other equipment to accomplish his planting. Going to no-till meant he did not have to buy large, more expensive tractors to till and plant all his acres. He found the sandy soils to be very conducive to no-till operations.

All crops grown on Dark Branch were centered around the tobacco crop. Tobacco was king and commanded the majority of everyone’s attention. In fact, Clegg was a tobacco auctioneer and sold tobacco in the warehouse for many years.

In 1978, Adam’s grandfather built several commercial turkey houses and started contract turkey production for Butterball. In the beginning, they were producing about 35,000 turkeys per batch, but later stipulations regarding space required per turkey, reduced those numbers to about 22,000 birds per batch. After adding the turkey houses, Adam’s grandfather quit growing tobacco and only Clegg continued the tobacco production. His grandfather also kept a few beef cows for some extra income, usually about 12–15 cows to produce calves each year.

In 1985, the family constructed hog barns for finishing pigs to harvest weight. They had hogs prior to that but production was centered on a farrow-to-feeder model. This was their first foray into contract finishing of hogs for vertically integrated companies. In 1995, Adam, who was 16 years old, obtained his first share in the farm with the contract hog farm. He was paid one-third of what the hog farm would produce.

Adam graduated from high school in 1997 and planted his first tobacco crop on three acres. He grew tobacco until 2015. During the intervening years, Adam expanded the farm’s land base and added some cattle for diversity.

In 1999, Hurricane Floyd hit them hard, causing extensive flooding across their farm. One of their primary concerns during the crisis was saving the pigs in the commercial hog barn. Luckily, the barn was built on an incline and they were able to push the pigs into the high end and save them from drowning in the floodwaters. Many of the pigs in the barn at that time were only about a week old.

After Hurricane Floyd, commercial hog farms increasingly came under public attack due to waste and odor pollution. North Carolina was one of the leading hog-producing states in the U.S. and several of the major vertically integrated companies were headquartered in the state. Due to the increasing public pressure, the state of North Carolina developed a buyout program and targeted certain farms for that buyout. There was a meeting scheduled to present the program to farmers in the area. Adam wanted to go to hear what was being offered, but Clegg was hesitant. Adam kept pushing his father to attend and he finally relented.

The program worked by identifying farms that were in high-priority areas for diminished production. Farmers would submit a bid for the buyout program and the state would select who to fund. Clegg purposefully submitted a high bid, hoping to discourage the state from funding a buyout of their farm. Ironically, they were number one on the state’s list for a buyout in their area and the bid was accepted. So, just like that Adam and Clegg were out of the hog business. The program required an easement to be placed on that tract of land to prevent operation of a confinement hog operation from that point forward.

For Adam, this was actually a relief. He found the confinement hog business to be frustrating, especially with the constraints imposed on producers, waste issues, and thin margins of profit. The buyout reduced Adam’s stress level and provided the father and son an opportunity to explore other options.

The buyout occurred in 2000 and Clegg used the funds to purchase a tractor and equipment dealership in Kenansville. Soon after, Clegg devoted his full-time efforts to the dealership and Adam, 22 years old at the time, took over full control of the farm on a day-to-day basis. Clegg gave Adam full control and supported him in his decisions and provided ongoing advice. Adam assumed a 50% ownership role in the farm.

About five years later, Adam started missing the hogs and decided he wanted to buy some pigs and start a small operation. Instead of building a confinement barn, he put the pigs out on pasture and in the woods to produce pastured pork. He initially bought five gilts and one boar. When neighbors and friends learned what he was doing, they were interested in buying pigs from him for harvest and buying pork. What most told him was they wanted pigs from the pastured system because that was how they remembered pigs being produced when they were growing up and it produced a wonderfully flavored end product.

Initially, the pork business was very local, but then Adam made a connection with some chefs who wanted better pork in their restaurants. Once they tried the pork they were enamored, and the growth of Adam’s new, pastured-pig enterprise was significant. In fact, one restaurant alone was using 35 finished hogs a week.

Adam took over the turkey farm from his grandfather in 2014. They were growing turkeys on contract with Butterball, one of the largest vertically integrated turkey companies in the U.S. He shut it down in 2016, even though he was in the top 10% of Butterball’s production efficiency standards. Surprisingly, he was grossing the same dollars as the turkey enterprise did back in 1979. Adam figured it was a losing proposition and he could make better use of the land and facilities. That was a difficult decision because his Grandfather set him up in the turkey business, thinking it would be a good income source for Adam.

Adam started growing corn, soybeans, and small grains in 1999. He also grew sweet corn and pumpkins to sell directly to consumers. From 2005 until 2017 he was practicing strip-till cultivation on most of the family farm. He had hit a wall with the no-till practices because they had not been implementing other soil health principles with the no-till, once again proving that no-till alone is not the key to regeneration. With the tobacco rotation, they were using full tillage once every five years, which included disking, breaking, and chisel plowing. Significant disruption to the soil was occurring each time they employed this extensive cultivation.

In 2010, they decided to start trying some cover crops on the tobacco acres only. The cover crop was a simple monoculture of either wheat or cereal rye. They would then chemically terminate the cover crop using an herbicide, strip-till and plant into the terminated cover. Roundup, a glyphosate, was the herbicide of choice. On the non-tobacco acres, they did not plant any cover crops. They would simply let the land lay bare and fallow after harvest until the next spring’s planting season started.

Another major milestone happened in 2015. For the first time ever, his hog sales surpassed his gross revenue for tobacco. Tobacco would typically gross between $3000 and $6000/acre. At their peak, Dark Branch Farms had 120 acres of tobacco, but Adam knew tobacco was coming under increasing scrutiny and he had already started losing contracts. In addition, he disliked the control that the tobacco buyers had over him. Adam decided he needed to learn how to farm without any of the tobacco acres and devoted much of his attention to the pastured-hog enterprise.

Regenerative Transition – The Beginning

The restaurant connections made through the pastured-pig enterprise eventually led to a connection with Ron Joyce of Joyce Farms. Joyce Farms is a family food business founded in 1962 as a chicken company that transitioned to a multi-protein company in 2011. Ron Joyce wanted Adam to produce pastured pork for Joyce Farms and be their primary supplier. At that point, Adam decided to stop trying to market the pastured pork himself and partnered with Joyce Farms in this effort.

That partnership initiated the meeting with Dr. Allen Williams of Understanding Ag, LLC. Ron asked Adam to meet with Allen and learn more about regenerative agriculture and discuss the pig genetics program. Adam reluctantly agreed and an initial face-to-face meeting was scheduled. When Allen showed up on Adam’s farm, Adam and Clegg listened politely, as is the southern way. But, deep down they had many questions about what Allen was telling them. As a matter of fact, the two later admitted they were “downright skeptical.” After Allen left, Clegg said to Adam “What that boy is telling you may work in Mississippi, where he’s from, but he doesn’t know beans about farming in North Carolina.”

Regenerative Transition: Jumping In

In the fall of 2016, Adam and Clegg planted five acres of multi-species cover crops (you read that right, five total acres) just to test what Allen had suggested. Due to their skepticism they were not willing to try more acres at that early stage. The cover crops were a success and they planted 37 acres in the fall of 2017, wondering if the success of their first planting of a multi-species cover crop was just a fluke. This second effort was so successful that Adam planted every acre on the farm in cover crops in 2018.

He went back to no-till in place of the strip-till at Allen’s urging. He has now been 100% no-till since 2016. By 2018, he had planted diverse covers on as many acres as possible. He learned about the “Rule of Compounding” and started experimenting with non-GM corn and soybeans. By 2018, 100% of his corn acres were planted in non-GM corn and he was experimenting with non-GM soybeans. Adam said he would have planted all his soybean acres in non-GM but was not able to get enough non-GM seed, so he planted GM soybeans on the rest of the soybean acres and treated both plantings equally. He was able to go to 100% non-GM on both corn and soybeans in 2019.

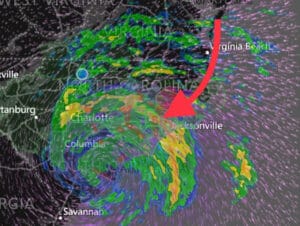

However, 2018 brought a challenge that the farm had not faced since Hurricane Floyd in 1999. In September 2018, an even more powerful storm, Hurricane Florence, hit them with 35 inches of torrential rainfall and covered much of the farm with 8–9 feet of floodwaters. At the time they had a very nice corn crop and soybean crop in the fields with cattle and pigs grazing multi-species cover crops.

These pictures show what the cover crops looked like prior to the flooding created by Hurricane Florence. Adam was doing quite well and was poised for a banner year with both the row crops and the livestock.

Flood waters besieged the farm and threatened the crops and the livestock. Luckily, Adam was able to harvest 90% of his corn crop just prior to Hurricane Florence making landfall. He was not quite so lucky with his soybean crop. They were not ready for harvest just yet. These pictures show the extent of the flooding.

The devastation wrought by the floodwaters was overwhelming. Adam lost his entire soybean crop, and all his cover crops and perennial pasture were heavily damaged. The picture shows what his soybean crop looked like just two weeks before the flood, while the other picture shows what the soybeans looked like after the floodwaters receded.

The cover crops he was depending on to carry him through the winter by supplying grazing for his cattle and pigs were heavily damaged. The picture shows what happened to the cover crop fields after the flood.

It appeared that Adam was done for the year. All his hard work with the regenerative practices were about to “go down the proverbial drain.” But as the floodwaters receded, he found that his soils responded with surprising resiliency due to the biology that had been built through just two years of regenerative efforts. The increased soil biology had created significant aggregation in his soils and they responded by drying out much more quickly than his neighbors’ farms in the region. Due to this, he was able to get tractors with no-till drills into his fields just two weeks after the waters receded. He replanted his acres with multi-species cover crops and had an immediate response. The biological resiliency caused quick germination of the seed and the plants responded with vigorous growth just two weeks after planting (Pictures 13 and 14). Within a month Adam saw a miracle occurring before his eyes. His fields were green again while all his neighbors’ fields were still brown and dead. His neighbors had attempted to get into their fields upon seeing Adam planting his fields, but were not able to because their soils would not support the weight of their tractors.

This experience cemented Adam’s resolve to go all-in on regenerative agriculture. Seeing what can happen when a person follows the “Six Principles of Soil Health ,” Adam has become a devoted advocate and talks with anyone who will listen about the benefits.

Combining no-till practices with diverse multi-species cover crops and then using livestock to graze those cover crops has proven to be a winning formula for Adam. In addition to the Six Principles of Soil Health, Adam has applied the “Three Rules of Adaptive Stewardship” (Compounding, Diversity, Disruption). He noted that through his heightened observation skills he has witnessed the power of compounding and cascading effects. As he increased his soil health practices, he realized significant positive compounding benefits.

Key Points of Progress

- In spite of the flooding caused by Hurricane Florence in 2018, Adam saved $200K in input costs using the Six Principles of Soil Health and the Three Rules of Adaptive Stewardship. By paying attention to his real fertility needs, and not simply following the recommendations of his fertilizer dealers, he experienced significant savings.

- In early 2018, he transitioned his cattle program to focus on the protocols for the Joyce Farms Grass Fed Beef program. He learned the importance of integrating livestock onto his row crop land by grazing cover crops. He also focused much more on his herd genetics. Working with Allen Williams, he culled some of his cow herd and purchased replacement females that were of higher quality. In addition, Allen helped Adam secure Aberdeen Angus bull genetics that allowed him to fully qualify for the Joyce Farms genetics protocols and their price premiums.

- He learned that some of his acres are better suited to livestock production and grazing than to row crop production. In the past, he would have pushed for maximum acres in row crop production but now understands that livestock can be more profitable and are valuable in improving soil health.

- In the spring of 2017, Adam purchased his first Gloucestershire Old Spot boars (a very old heritage breed of pig originating in the British Isles) from Teddy Gentry (of the country music group Alabama). These boars became the seed of the Joyce Farms Old Spot line of pork.

- Working with Joyce Farms, Adam produced an initial set of harvest-ready pigs for Anheuser-Busch and Baldor (a specialty food distribution company). This group of harvest-ready pigs totaled 85 but grossed as much money as 2.75 flocks of turkeys. That confirmed Adam’s earlier decision to get out of the commercial turkey business and transition to pastured-pig production.

- In an effort to help other farmers make the regenerative agriculture transition, Adam and his family hosted a Soil Health Academy in 2018 and hosted a portion of an academy in 2019.

- Adam has hosted a workshop and several Joyce Farms Tour events. With the Joyce Farms tour events, Adam has played host to more than 300 chefs and food distributors. Those in attendance have hailed from all the way to New England, down to Miami, and as far west as New Orleans and St. Louis.

- In 2019, he was convinced of the benefits of regenerative agriculture and of the need to fully change his focus. He not only planted multi-species cover crops on all his row crop acres, but he experimented with terminating his cover crops by rolling and crimping them and no-till planting directly into the roll down. He invested in a roller-crimper and transitioned from a 12-foot conventional till drill to a 15-foot no-till drill. These changes allowed him to reduce his workload significantly. Now he simply plants his cover crops, rolls and crimps them, and plants into the matted cover crop. This greatly reduced the need for multiple tillage passes, thereby reducing labor, fuel, wear and tear on equipment, and maintenance costs. This also allowed Adam to downsize his equipment and replace old larger tractors with newer, smaller tractors. He also realized that moving smaller equipment down the public roads was far easier and safer than the much larger equipment he once owned.

- In 2019, he was able to significantly reduce his applied fertility needs. On one 25-acre field of corn, for example, all he had to apply was just a small amount of nitrogen with no applied phosphorus and potassium. He obtained most of the nutrients needed from the prior cover crop.

- In 2019, Adam was able to transition completely from GM seed to non-GM seed. This allowed him access to non-GM markets, including Joyce Farms, that proved to be more profitable.

- The year 2019 was one of prolonged heat and drought. That year taught Adam that regenerative agriculture is about the total picture and not just no-till planting and cover crops. Using his multiple species of livestock, now composed of cattle, pastured pigs and hair sheep, Adam turned cover crops into revenue by grazing them and by feeding the non-GM grains back to the pastured pigs. These multiple revenue streams from the same acres allowed Adam to pay off all personal debt, with the exception of one small farm he had purchased several years earlier. Because of this, he was able to purchase another new farm with cash. He also bought several new pieces of equipment and lived comfortably through the year. In addition, his family enjoyed their first vacation in 15 years. In the midst of a challenging year from a weather standpoint, Adam paid all of farming expenses and made the most net profit he had ever made.

Lessons Learned and Surprising Reactions

- Adam experienced significant pushback from the agricultural supply companies he did business with. This included the fertilizer, seed, and chemical companies. They did not like him straying from their recommendations and making his own decisions.

- The seed companies strongly advised him against using non-GM seed and even tried to price him out of the market. They so inflated the non-GM seed that his price quotes were as high as $299 per bag. He ended up going with a company that specialized in conventional seed and his final price was $200 per bag cheaper than the quotes from the other seed companies. They were doing everything possible to keep Adam from transitioning to non-GM crops. The parent seed companies controlled the local dealers and their price was the same to Adam no matter which company he received quotes from.

- Adam learned to break his addiction to doing things the conventional way and trying to be like his neighbors. He learned to ignore the pressure from dealers, suppliers, and neighboring farmers.

- Adam and Clegg were extremely skeptical at the beginning, but are “all-in” now. The conviction that Understanding Ag and the Soil Health Academy instilled in Adam convinced him to play a role in passing it on. He has become a huge advocate for regenerative agriculture and discusses the benefits with his neighbors and anyone who will listen. The results speak for themselves, especially the changes they are seeing in their eastern North Carolina sandy soils.

- His family has been surprisingly supportive. Though skeptical at first, they are all now fully engaged. Initially, Adam asked his father to watch Understanding Ag videos and then asked him what he thought. Clegg watched carefully what Adam was doing and started studying Gabe, Ray, David, and Allen. He is now a “believer.” Clegg certainly understands the financial benefits. In 2019, the farm’s profit was more than 100% above any previous year’s profits.

- Adam’s grandfather was skeptical, but had not been out to the farm to see much firsthand. One day, he got in the truck and rode with Adam. He said he really liked what he saw but told Adam, “You’ve created a problem.” The farm was now green, clean and great looking but his grandfather told Adam that everyone would be trying to buy their farm. Adam responded that the family held the deed to every acre and controlled their farm’s future. That conversation happened shortly before his grandfather died.

- Adam now has a supporting network of mentors and other farmers who are also journeying down the regenerative path. These folks are valuable to Adam in providing encouragement and sound feedback and advice.

- On their leased land, the Grady’s are getting great reactions from their landlords. The landlords have even participated in the farm tours and have been eager to learn more about regenerative agriculture. They appreciate the positive changes to their land and the fact that Adam is creating better soil health profiles and ecosystems.

- Adam’s reaction to being able to learn from Understanding Ag and the Soil Health Academy has been simply “Thank You.” It would have been easy for Adam to keep doing things the same way. It took courage and conviction to make the changes he did. Adam decided that it was his business and his family. Because of that, any supplier or dealer had to start earning his business—not simply living comfortably at Adam’s expense.

- Adam has been effective at influencing a number of his neighbors who have also participated in the Soil Health Academy and have started their own regenerative agriculture journey.