In my previous post, I discussed building soil aggregation and how this can help to address some of the problems growers face today. Those stable aggregates are created by living plants that release root exudates to feed a diverse quorum of microbes in the soil. The more the diverse the living plants are, the more diverse the microbes are. When one species of plant is releasing exudates to feed a set of microbes that are good at providing zinc, let’s say, another plant may need boron and will release exudates for signaling microbes to help facilitate in the exchange for boron. This happens for all of the nutrient’s those plants require. So, as we add diverse cover crop mixes to our fields, and as long as we do not remove the above ground plant material by means of haying, we can actually cycle those nutrients back to the next growing crop.

Cycling Nutrients

Farmers across much of the Midwest and south have a greater opportunity to cycle more nutrients through a cover crop because of their longer growing seasons. They can allow the cover crops to mature longer. Bigger cover crops equal more biomass per acre. More biomass per acre means more nutrients were taken up by those plants. More nutrients in the above ground biomass means that we can begin earning the right to cut back on certain fertilizers and save money.

But we also have to pay attention to some key measurements in the soil such as CO-2 respiration and C:N ratios of the biomass to understand if the crops will mineralize (release those nutrients back out in a timely manner) or immobilize (tie the nutrients up in the microbes and not allow them to cycle back out to the next crop). This is critical in understanding how we can take credit for certain nutrients cycling and how to design cover crop mixes for the next cash crop. We have a protocol that we use within Understanding Ag to measure soil biological activity, soil nutrient availability, nutrients in the biomass, and nutrients mineralized out of the biomass to be taken up by the next cash crop. The results from these tests are mind blowing and tell us how much fertilizer we need to apply.

In the northern environment, this practice is not as practical with the shorter growing seasons. This is where having a summer-harvestable cash crop followed by a cover crop can be used to build biomass the year prior to the next cash crop. In some areas of the north, it is more practical to open the sieves on the combine a bit and allow some grains to spread out of the back of the machine and reseed themselves to keep a living root in the ground as long as possible. This can be used as a cover crop.

A Look Ahead for Cover Crops

On February 7, 2022, Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack announced a $1 billion competitive grant offering to fund pilot projects through its “Partnership for Climate-Smart-Commodities” program. What could this mean? For starters, a lot more money for cost-share programs for cover crops. Their goal is to double the number of acres with cover crops by 2030. This is a good thing though, right? That is a tricky question. The retention rate of most of the subsidized conservation practices like cover crops is less than 10% nationally. Most of this is due to the lack of education and understanding of how soils were designed to function, how cover crop mixes should be designed and managed, and how to measure and test results with on farm trials. But the biggest challenge becomes with seed supply. The summer of 2021 was incredibly dry in parts of North America where a lot of the cereal grains are produced such as cereal rye, triticale, barley, oats, etc. So, in the fall of 2021 the price of these cover crops increased considerably. Now, couple that with the rising price of wheat on the board of trade. Farmers had to make decisions to grow wheat or rye. Often, these farmers can produce 100-plus bushel wheat whereas cereal rye may at best only produce 50 bushels. So, for rye to compete with the wheat acres, the price of that needs to be increased as well.

Between the summer of 2020 and 2021, the heart of Oregon where a lot of legumes, brassicas, and ryegrasses are produced, went through either incredibly wet times during harvest in 2020 or incredibly droughty conditions throughout the summer of 2021. Now let’s add on fuel surcharges and issues finding trucking outfits to haul product from the pacific northwest to the corn belt or eastern half of the United States. See where things are going to start getting hairy? Prices of cover crops and supply could be extremely limited in the fall of 2022. Here’s a hint, if you have something growing as a cover crop this spring that you can harvest and have cleaned, you may want to consider how many acres you might need to leave for production this year. I predict that cover crop supply will only get tighter in the coming years and seed prices will continue to increase. This will also represents an opportunity for farmers to diversify their farming operations as well.

The Link Between Diversity and Disease

With diseases in crops becoming more prevalent, we should be asking ourselves why? Some of these diseases are actually a symptom of a nutrient imbalance or deficiency in the plant while others reside in residues. Some diseases are fungal while others are bacterial. This is important to note as a fungicide has little effect on a bacterial pathogen. Across the Midwest, Tar Spot has become a common fear. In 2021, some claimed that Tar Spot reduced yields by as much as 50 bushels per acre. But ironically, I have spoken to some who did not spray any fungicide for the Tar Spot while their neighbors did, and the comparable corn yields were nearly the same. Maybe environmental influences of too much rain early in the season or too dry after kernel set had more to do with the yield variance than the actual disease. In the south, southern rust on corn can cannibalize a plant and this disease can take a lot of yield. I am in no way saying to not spray fungicide. If you need it to protect your crop, use it. But I would suggest scouting and leaving check strips in the same field, so you’ll know if the application of the fungicide paid off or not.

Grey Leaf Spot is a common pathogen that is sprayed at tassel time. Often, across the Midwest, aerial applicators begin flying in early July to protect against this disease. The pathogen resides in corn residues as well. University publications recommend managing corn residues through tillage practices. Thinking back in time a bit, I do not recall as much focus on managing foliar diseases in crops. But we also had much different cropping systems. It wasn’t until the demand for ethanol grew beginning in 2005 that many of the cropland acres were planted heavily to corn. Prior to 2005, many farms were much more diverse in their cropping rotations. Wheat was in nearly every farmer rotation. With a three-year crop rotation across many acres, there was not as much demand on the soil for producing high yields and the diversity of crops allowed for more microbial diversity in the soils.

Now, when driving across the Midwest, and surprisingly across the country, I see miles upon miles of corn and soybeans. This is not a rotation but rather a pendulum swing back and forth. Many of these acres are corn-on-corn with soybeans in the rotation maybe every third year, but sometimes not until the fifth year. Based on the practices implemented, microbes will quickly thrive in our fields.

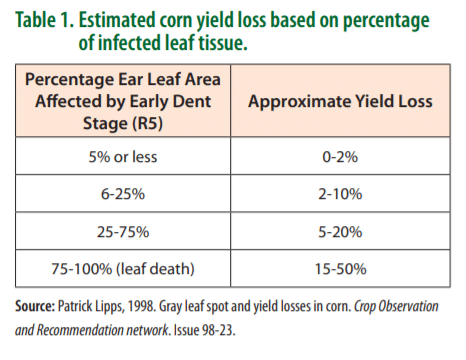

It is no wonder we see more diseases because the crop rotations that provide microbiological protection are no longer in place. We also see more nutritional deficiencies with less cropping diversity. The excess of some nutrients, especially nitrates in plants, cause many diseases and insect isses. Integrated Pest Management applies to all pests including pathogens, insects, and weeds. Instead of broad-acre applications, a lot of money could be saved by scouting fields and determining if there is an economic threshold for an application to be made. Here is an example of the expected yield loss due to Grey Leaf Spot on the ear leaf of corn. Sure, when corn is $3.00 a bushel compared to $7.00 a bushel, it requires a lot more bushels saved to justify the expense, but as the price for a bushel of grain has increased, so has the price of the inputs and the application methods. A sharp pencil is going to be required in 2022 to justify any applications.

Critical Management Decisions Ahead

So here we are in March, and farming is looking rather frightening with input expenses and uncertainty in the marketplace. Fuel prices for red diesel have increased $1.19 a gallon since last year at this time. What can we do now? The quickest way to reduce the cost of production this year is to try no-till. The reduction in fuel and labor will have a major impact on the bottom line. Custom farming rates for chisel plowing, and soil preparation with a vertical tillage tool or field cultivator will cost upwards of $60 or more an acre for just three passes across the field. No-tilling alone can save you that expense. If there is no cover crop sown yet, there is still time in parts of the Midwest to plant spring oats and even spring peas or vetches if a nitrogen source is needed.

I would recommend leaving the legume out if going to a legume cash crop. This can help to begin the aggregation building process. These species are also highly mycorrhizal which can help to solubilize and cycle organic phosphorous from the soil profile. With the added residue on the soil surface, we may be able to suppress weeds and cut out a sprayer pass. If we have a wet spring, these crops will continue to use water as they grow. But if they are killed early and we have a wet spring, the soil may remain saturated longer as there is no living root in the soil to take up the water and the matt of residue will keep the soil from drying. On the flip side, in environments that tend to be dry in the late spring, these cover crops may need to be terminated earlier to avoid them taking up plant-available water out of the soil profile that is needed for the cash crop. The longer the legumes are allowed to grow, the more nutrients could be cycled if C:N ratios are managed for soil microbial activity.

The Bottom Line

The bottom line for your bottom line, this year especially, is to do everything possible to enable your soil to function for you. The best way for your soil to function is to create a habitat below ground that will make trillions of your unseen business partners (soil microbes) happy and eager to work for you (see Understanding Ag’s 6-3-4TM soil health-building principles in Part One of this series). And in addition to providing a host of production, nutrition and plant-protection benefits, these microbes work for free.