In part one, I outlined some of the societal challenges linked to soil erosion and poor soil function. Now let’s take a look at some of the economic costs and benefits of addressing erosion on farms and ranches.

To determine the cost of erosion, first we must assign a value to soil. In truth, topsoil is priceless because it is what enables most life to exist on this planet. Academic discussions (including mine) about the cost of erosion and value of soil gloss over the fact that we cannot survive without it. How do we put a price on life?

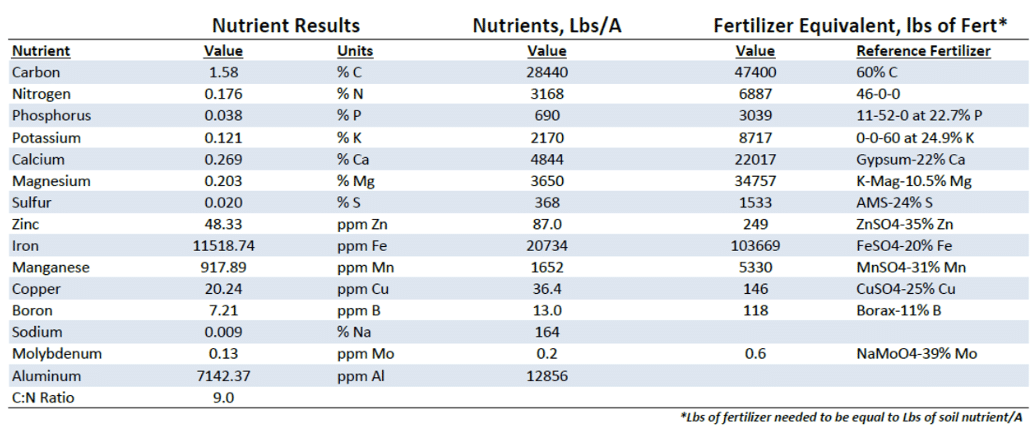

For the purposes of this exercise, let’s assume that we could purchase more topsoil if it eroded away. One common way to put a value on soil is to determine how much fertilizer it would take to replace the lost nutrients. Again, this is disconnected from reality, but it gives us a starting point. You can run a total nutrient digestion (TND) test on your soil to get a breakdown of what it contains. An example from our family farm is shown below. For reference, this is a silt loam soil with just over 3% organic matter in the top 6 inches.

Figure 1. Results from a total nutrient digestion soil test.

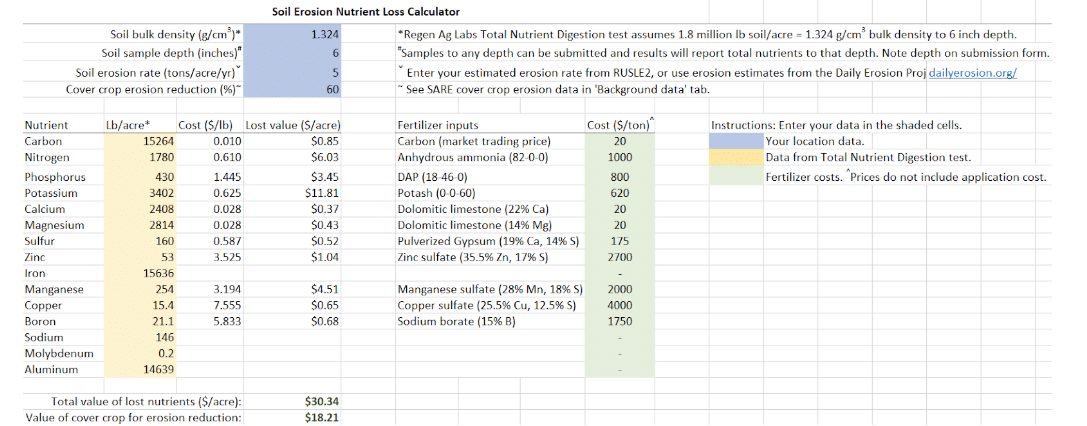

I created a spreadsheet to take the numbers directly from this test and calculate a value per ton of soil based on average fertilizer prices over the past several years. To determine the cost of erosion, I used the NRCS tolerable soil loss or “T” value for our farm of 5 tons per acre. The Daily Erosion Project and other research has shown that this is roughly the average soil loss per acre in the Midwest. These estimates are complex because they depend on models to predict soil loss. Not all soil that ‘erodes’ from a field actually leaves the field. Some soil just moves down the slope with water and settles out at the bottom of the field. Some leaves the field and ends up in ditches or waterways, and some soil is picked up by wind and deposited elsewhere. Despite the complexity, 5 tons per acre per year is a reasonable estimate for the Midwestern U.S. Actual erosion rates are likely much higher across the Midwest this year due to heavy rainfall events.

In the calculations, I put a small value ($20/ton) on soil carbon and I also valued the major micronutrients. Plugging in the numbers with an erosion rate of 5 tons/acre results in a cost of about $50 per acre per year in lost nutrients. Your cost may be higher or lower depending on soil fertility and erosion rates, but $50/acre/yr is an alarmingly high number in my book. The actual number would be higher because the soil that erodes away is from the very top of the profile where organic matter and nutrient concentrations are highest. I am just using the average nutrient concentration in the top 6 inches of the soil profile. As mentioned earlier, this number grossly undervalues what soil is really worth. The reason we consider this rate of erosion to be “tolerable”’ is because no one actually has to write a check for $50 per acre every year as an erosion tax while their soil disappears.

Out of curiosity, I entered the values from a TND test taken in central Kansas in sandy, 1.7% OM soil for comparison and got a cost of $30/acre/yr with 5 tons of soil loss (Figure 2). I added the fertilizer values a few years back so prices may be higher or lower now.

Figure 2. Soil erosion cost and cover crop value calculator based on values from the total nutrient digestion soil test.

Adding a cover crop is one option for reducing erosion and keeping more dollars in farmers pockets. Research shows that adding a cover crop to a row crop field can reduce soil loss by about 60% on average. What’s the value of that? Using the $30-$50 per-acre estimate for the cost of erosion, the cover crop keeps $18-$30 worth of nutrients in the field that would otherwise be lost. That is just one value of a cover crop.

Water quality research from the Upper Midwest shows that a winter cereal rye cover crop reduces nitrate leaching by around 30%. This equates to a reduction in N loss of around 10-15 lb N per acre per year in a tile-drained field. You might be thinking that doesn’t apply if you don’t have tile drainage, but high nitrate wells all over the Midwest in areas with no tile drainage prove that we have been losing nitrate to deep groundwater for decades. Preventing this nitrogen loss is worth around $10 per acre (depending on N prices) if you didn’t have to repurchase what was lost. This nitrogen loss may not be noticeable year to year, just like soil erosion is not noticeable in the short term, but farmers are indeed paying the cost of soil and nutrient loss in the form of higher fertility bills and lost yield.

Adding the erosion reduction and nitrogen savings gives us a cover crop value in the neighborhood of $25-$40 per acre. This ignores the multitude of other benefits that come with keeping a living root in the soil throughout the growing season. We have to ask: Are cover crops really an expense, or are they actually a dividend-paying investment that saves money and improves soil productivity over time?

The value that cover crops provide is far greater than just preventing erosion. Cover crops provide a way to keep a living root in the soil throughout the growing season, and living plants are the only way to feed soil biology and build soil aggregates. Well-aggregated soil allows for improved gas exchange, water infiltration, and compaction resistance. Biological activity in the soil is what drives a vast majority of nutrient cycling and nutrient uptake by plants. Cover crop mixes also provide much needed diversity to monoculture cropping systems. It is well established through research that more diverse rotations provide economic benefits via improved yields and reduced pest and disease pressure. Plants, working with their biological partners in the soil, provide the carbon source for increasing organic matter levels and making the soil more resilient in the face of extreme temperature and moisture fluctuations.

Even this overly simplistic, reductionist view of the cost of soil erosion shows that it is something we cannot afford to ignore. The actual value of regenerative land management is orders of magnitude greater when we factor in the improved ecosystem services that result. Benefits like cleaner air and water, less pollution, better food, and a healthier environment full of life-sustaining diversity are invaluable.

Hopefully this thought experiment helps us to stop and think for a minute about the true cost of poor land management, the benefits of implementing the soil health principles and following the rules of adaptive stewardship to improve ecosystem processes on our farms and ranches.

Soil, and the water that flows through it, is the foundation of life. Currently, many farming and ranching practices are allowing soil to erode away and water to become polluted. As farmers and ranchers, we can choose a better way, and as consumers, we can demand a better system. If we don’t, we can expect the same outcome realized by previous civilizations that collapsed under the weight of environmental degradation. We are part of nature, and we must learn to farm in harmony with it. Because failure is not an option.