There is an interesting and thought-provoking quote from Masanobu Fukuoka, a Japanese farmer and philosopher renowned for his natural farming, that is quite pertinent to climate resiliency. The author of The One Straw Revolution, Fukuoka states, “It was in an American desert that I suddenly realized that rain does not fall from the heavens – it comes up from the ground. Desert formation is not due to the absence of rain, but the rain ceases to fall because the vegetation has disappeared.”

This quote from Fukuoka solidified what we have been observing and noting for many years: The vast majority of deserts globally were not always deserts. Most were once-thriving grasslands and forests that, through mismanagement by man, have become deserts. This is certainly true of North Africa, the Southwestern U.S. and much of Mexico.

Epic droughts, wildfires so intense that they create their own weather and tragic flooding are all a part of our own creation—by failing to properly manage or steward what we have been blessed with. Soils that cannot infiltrate and retain water lead to either flooding or drought, and in many cases both. In the Western U.S. in 2021, we have seen extreme and exceptional drought, coupled with cloudbursts that caused massive erosion--resulting in drought-to-flooding conditions in mere hours.

The good news is there is something we can do about this situation. Our management of the land matters and it can make a huge difference in how the land and atmosphere responds. There is a growing body of evidence that supports the contention that regenerative management is a game changer on the ground and in the sky.

Rainmaking Microbes

Microbes are everywhere, including in the clouds. Scientific studies are now showing that they play an important role in creating precipitation (reference links to multiple related articles are provided at the end of this article). Microbes from the soil and plants can go airborne and facilitate a process called bio-precipitation. These microbes include bacteria, fungi and tiny algae.

For a cloud to produce precipitation that falls to earth as rain or snow, ice particle formation in the clouds is required. Just a decade ago it was thought that only small mineral particles, or other inert particles, could serve as nuclei for condensation to occur. However, we now know that aerosols in the form of microbes can catalyze ice particle formation that trigger precipitation.

The evidence is building that vegetation and soils are a crucial source of atmospheric biological ice nucleators in precipitation. They may, in fact, be the most efficient ice-forming catalysts in precipitation, not airborne mineral particles. These “rainmaking” microbes are significant influencers of the water cycle. They can also travel long distances in the atmosphere for dispersal on a global scale.

Now we know there are trillions of airborne microbes that perform this task as well. They even do it better than mineral particles because they catalyze precipitation at higher temperatures than the mineral particles. This means the clouds do not have to be as cold before ice-nucleation can occur. The evidence also shows that microbes travel great distances in the clouds, across oceans to other continents. This strongly suggests that biology-derived precipitation occurs around the globe.

Some of these ice-nucleating microbes are plant pathogenic bacteria, such as Pseudomonas syringae, that can cause disease in crops. However, where there is plant species diversity and greater crop rotation facilitating enhanced plant resistance and resilience, this is far less of an issue. As a matter of fact, scientists now believe that the process of microbes going airborne and being disseminated through precipitation is a core facet of their life cycle and allows them to colonize to new plant hosts. These airborne microbes can also metabolize and grow population numbers while in the clouds.

Rain in the Desert

The Chihuahuan Desert of Northern Mexico, Southwest Texas, and southeastern New Mexico, typically receives about eight inches of rainfall annually, all within a short “rainy” season of three months. The rest of the year it is dry. This has been the norm for many decades now, but this desert once was a thriving grassland that supported large herds of bison, elk, and antelope, along with predators such as the Southern Gray Wolf, Mountain Lion, and Grizzly Bear. Historical accounts also state that there were abundant beaver and river otter across the region.

Today, the Chihuahuan Desert bears no resemblance to that thriving grassland. Most ranches in the region require 150 acres or more to support a single cow/calf unit. Because water is scarce and a limiting resource in grazing livestock, the ability to capture and retain moisture is key to ranching success.

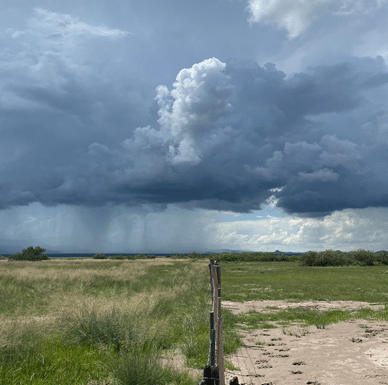

Today, there are ranches in this vast desert that are not only infiltrating and retaining most of the precipitation that does fall, but they are now creating their own rainfall through regenerative practices. The evidence has been stacking up for the last 4-5 years and the impact of the “greening of the desert” has affected weather patterns over these ranches.

Las Damas Ranch

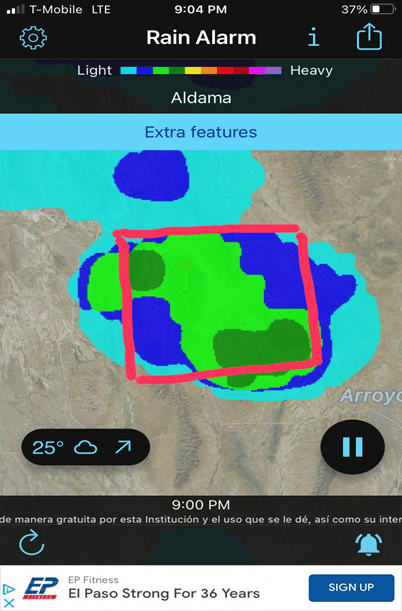

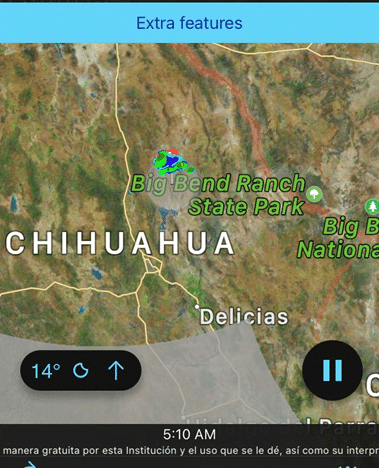

Multiple-year radar data and actual measured precipitation indicate that the vegetation being produced on these regenerative ranches is generating rain that is highly concentrated over these green areas (Picture 1). The average rainfall for this region has averaged seven inches for the past three years. That rain comes within a short 2-3 month period, accompanied by a long, 9-10 month dry period. Therefore, it is critically important that ranches in this desert first get as much rainfall as possible and then capture that rainfall through infiltration.

Seven inches on one ranch does not produce the same results as seven inches on another ranch. Fore example, if Ranch 1 has been implementing regenerative practices and can infiltrate the majority of that seven inches, their results are far different than Ranch 2 that manages conventionally and infiltrates 50% or less of that seven inches.

The ranches in these case studies have averaged between 1-2 inches additional rainfall compared to the regional average. For many of us that may not seem very significant. However, in the desert where seven inches is the annual total, receiving one more inch is a 14% increase. Getting two more inches is a 28% increase.

More importantly, these ranches have infiltrations rates that average 300% greater than neighboring ranches. So, not only are they getting more total rainfall, they are keeping significantly more of that rainfall. In addition, these ranches are observing a higher frequency of heavy morning dews. While it is very difficult to measure the amount of moisture in a dew, even trace amounts of moisture can be moved into the soil profile. By maintaining significantly more plant residue compared to their neighbors, much of the dew on the regenerative ranch does not evaporate, but infiltrates. On neighboring ranches, however, most dew evaporates quickly after the morning sun heats up the atmosphere.

Some areas of neighboring ranches are benefitting by proximity from this increase in rainfall on the regenerative ranches. Neighboring ranches on the trailing edge of these rainstorms are getting more rain on those portions of their ranches, until the energy of the rainstorm plays out. We have also noted some marginal benefit for neighbors on the leading edge as well. Unfortunately, the neighboring ranches cannot take advantage of this additional rainfall as well as the regenerative ranches due to poor water infiltration capacity.

The radar image below captured by Alejandro Carrillo on his cell phone shows the high concentration of rain occurring centrally on his ranch, located in the municipality of Aldama in Chihuahua, Mexico. The heavy concentration of rain is directly over the grasslands Alejandro has restored through his regenerative grazing practices. He has been observing these patterns for the past several years now. For many years, his neighbors accused Alejandro of getting more rain than they did, using that as the excuse for why his pastures were so much better than theirs. Initially, that was not the case, but now Alejandro truly is getting more rain than the neighboring ranches.

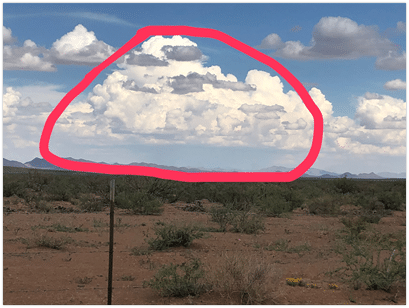

Alejandro has carefully documented the formation of storm clouds over his ranch where little-to-no storm clouds form over his neighbor’s ranches (Picture 2). This has been happening with more frequency over the past four years.

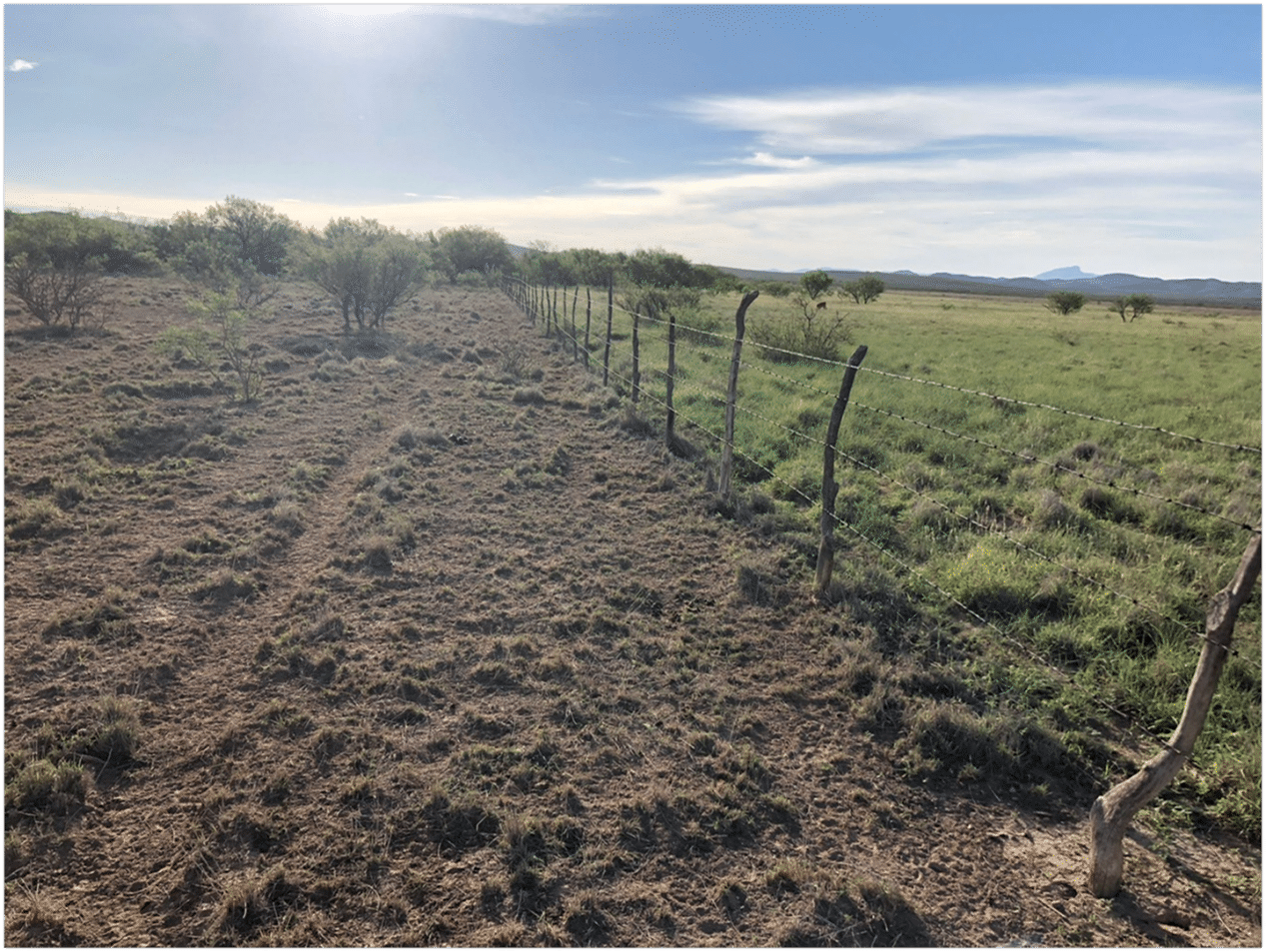

Other regenerative ranchers in northern Mexico have experienced similar results and weather patterns. The Parritas Ranch, in the state of Chihuahua, is getting rains that their conventional neighbors do not. Often, this provides a very stark contrast as noted from the picture of a fence line comparison between the Parritas Ranch and the neighboring ranch (Picture 3). Perhaps a partial explanation resides in rain-making microbes?

Rancho El Refugio in Chihuahua is also reporting encouraging weather results from their regenerative efforts. Similar to Las Damas, radar images show rains centered over the ranch with little else showing up on the radar within a 200-mile-plus radius (Picture 4).

Like the Parritas Ranch, Rancho El Refugio also has a stark fence line comparison that shows far more green, growing plants on their side of the fence compared to their neighbor (Picture 5). Yes, their grazing management is significantly better than their neighbor’s management, but they are also creating the conditions for precipitation to occur more frequently.

Picture 6 shows a fencline comparison between neighboring ranches, one managed regeneratively and the other managed conventionally. This comparison illustrates the benefits of water infiltration and retention. Just as important as how much rain a ranch may get is the amount of rainfall they keep through improved soil infiltration.

Each of these ranches has fully implemented regenerative principles and practices and all have experienced significant improvement in net profits, forage biomass production, plant species diversity—and they’ve increased their livestock numbers on the same acres. Their ecosystems are substantially better, as evidenced by an explosion in beneficial insect and bird populations, as well as many other wildlife species. Conservation groups have documented a number of endangered bird species that are now thriving on these ranches. They include the Sprague’s Pipet, Piping Plover, Lark Bunting, Chestnut Collared Longspur, Svanna Sparrow, Vesper Sparrow, Brewer’s Sparrow, Baird’s Sparrow and Aplomado Falcon.

Summary

New evidence and research regarding the impact of soil microbes on the creation of precipitation can be accurately characterized as a game changer in our understanding of what it takes to produce rain across the globe. The immediate question is: What can we do to create favorable situations for this ice-nucleation cycle to occur? The answer resides in managing more acres regeneratively. The evidence presented from Chihuahuan ranchers is both strong and compelling. What they are observing and documenting, is not happenstance or mere correlation. It has occurred far too often and too consistently for that to be the case.

It’s increasingly clear that when it comes to rainmaking (and rain retention) we reap what we sow—in the soil and in the sky.

References:

- https://sciencenordic.com/climate-denmark-videnskabdk/bacteria-in-the-atmosphere-cause-rain/1423395

- Potential Sources Of 'Rain-Making' Bacteria In The Atmosphere Identified -- ScienceDaily

- 'Rain-making' bacteria found around the world | Nature

- Evidence Of 'Rain-making' Bacteria Discovered In Atmosphere And Snow -- ScienceDaily

- Surprising Find: Live Bacteria Help Create Rain, Snow & Hail | Live Science

- Radical ideas: Bacteria controls the weather - BBC Science Focus Magazine