When I began studying ornamental horticulture and landscape design over 25 years ago, regenerative agriculture was just a twinkle in Gabe Brown’s eye and a glimpse of the future in the eyes of Allen Williams’, Ph.D.

For me, well, I was taking an introductory soil science class in a two-year horticulture degree program at Farmingdale State College on Long Island, NY. In that soil science class, I learned all about soil horizons, particle size ranges that comprise sand, loam, and clay, pH, N,P,K, and the fact soil compaction inhibits plant growth.

Today, following many years in both the landscape design/build business, while also raising and marketing 100% grass-fed beef and registered Angus breeding stock, I’ve learned some more about soil science. That knowledge didn’t come from the plant science and landscape design course of study I continued in at Cornell University, though. It came from putting into practice what I was learning about adaptive grazing, cow nutrition, raising environmentally adapted cattle, and epigenetics from Allen’s and Gabe’s sharing their hard-earned and hard-learned lessons, as well as their insights.

Now, as I design landscapes for my residential clients close to home—and work with farmers and ranchers as a consultant with Understanding Ag—I see better how we can’t really parse out the home landscape “flower beds” from the vegetable garden, or either of those from the 1,000-acre fields of wheat or corn in the Midwest and Great Plains. The principles of soil health bind all together. They are natural phenomena which some have been clever enough to discern and codify so the rest of us can better understand how to work with them as guides in our farming, ranching, and even landscaping ventures.

What does a regenerative ornamental planting look like in a residential setting? The answer, as it is to so many questions is, it depends.

Context, the first of the Six Principles of Soil Health™, dictates nearly all the practices we’ll recommend or implement during the design phase of any landscape. What does the site tell us about available sunlight, drainage, elevation, history of the soils on site, etc.? How do the answers to those questions influence the homeowner’s likes and dislikes, “issues” that need to be solved and what are the wants and needs of the homeowner, which also are part of the context within which we are designing and planting?

We can start by doing the same things we do in a row-crop or small-grain field. We take soil samples in order to test the overall status of soil health and biology, we make observations of current conditions of plant health, we measure water infiltration rates, and make observations of slopes, erosion, weed pressure, etc.

Then we go to work thinking about the palette of plants that will work to improve the health of the soil while also meeting the client’s wishes for the appearance of the home or commercial property.

Just as we do by cover cropping with annuals in advance of row cropping, or even in advance of perennial pasture establishment, we can use cocktail mixes of warm-season annuals and cool-season annuals in advance of creating ornamental planting beds. Following the Rule of Diversity, we will utilize representatives of different plant functional groups: grasses, legumes, forbs, woody plants. This diversity of plant groups helps foster diversity in our soil microbiology as well as a diversity of plant root types and structures.

We can also go straight to planting our ornamental beds with the desired perennials, woody plants, and annuals using the same thinking in terms of choosing representatives of different plant functional groups.

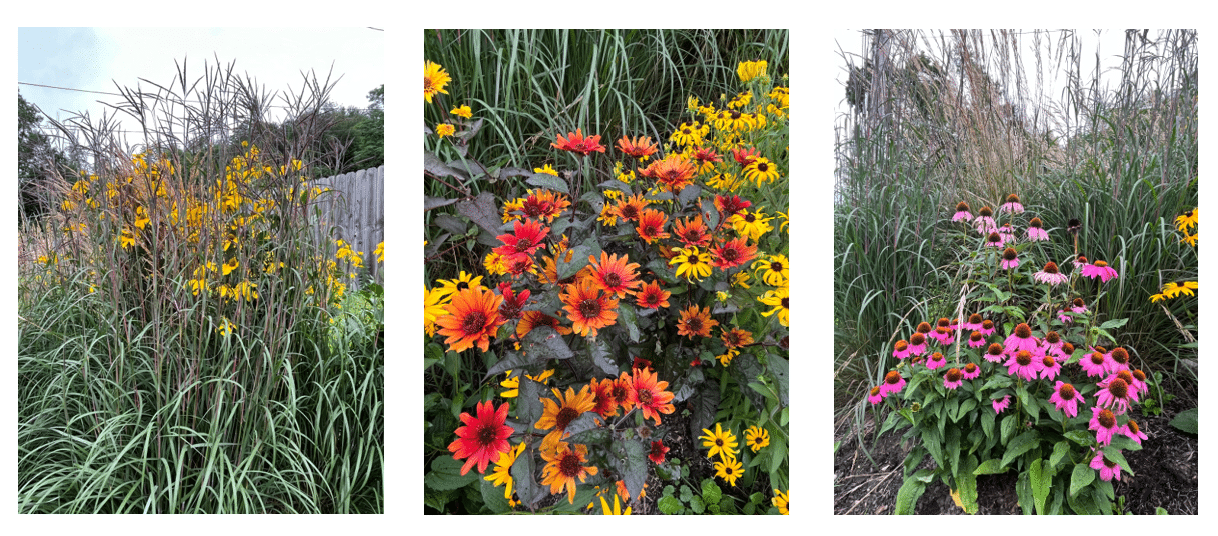

The photos below are of examples of going directly to planting after stripping turf from a portion of this lawn at my own home. The lawn turf is a mix of Kentucky 31 tall fescue, Kentucky bluegrass, naturalized Dutch white clover, ground ivy, dandelions, and various other species. This lawn was “inherited” by us when we purchased the property.

Above is a photo of a very low-maintenance “prairie planting” in the Berkshires of Massachusetts: Andropogon gerardii ‘Blackhawks’ big bluestem, Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’, feather reed grass, Echinacea purpurea, ‘Pow Wow (R) Wild Berry’ purple cone flower, Heliopsis helianthoides, ‘Yellow Spider’, false sunflower, Heliopsis helianthoides, ‘Bleeding Hearts’, false sunflower, Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii ‘Goldsturm’, Goldsturm black eyed susan, Rudbeckia hirta, ‘Indian Summer’, Indian Summer black-eyed Susan, Rudbeckia nitida ‘Herbstonne’, Autumn Sun giant coneflower.) The bed is 22’ x 8’, full sun/part shade, south facing, sloped, clay loam soil, pH 6.4, compacted. No soil amendments, no herbicides, no pesticides, no fungicides ever used. Planted densely to; allow upright and stiff-stemmed grasses to support tall growing flowers and grasses which tend to “flop”, suppress weeds, attract birds and beneficial insects.

This particular bed will expand from its current size and composition to cover about 1,000 sq. ft. and will have a number of new species added: Joe Pye weed (Eutrochium), elderberry (Sambucus), switchgrass (Panicum), prairie drop seed (Heterolepis), swamp azalea (Rhododendron), phlox, (Phlox), New England aster (Symphyotrichum), wood aster (Eurybia), and hairy vetch (Vicia).

Other annuals which can be added as plugs or by seed are zinnia, oats, cosmos, phacelia, purple fountain grass (annual in my USDA hardiness Zone 5)

From a homeowner point of view, this type of planting in an otherwise unutilized part of the landscape has the benefit of looking truly beautiful for many parts of the year and can be as intensively managed as one wants, or doesn’t want. I think of these unutilized or underutilized areas as mimicking the ‘edge’ habitats that appear at the borders of clearings in the woods, areas that get more sun than under the canopy, but which are not outright grassy areas. Hedgerows between farm fields provide a similar type of habitat and create yet more diversity to the system as a whole.

Further, the fact this type of planting attracts a wide variety of pollinators, both native and introduced (think bumble bees vs. honeybees), along with beneficial predatory insects and all sorts of birds, and helps minimize reliance on pesticides in our more highly-managed ornamental and vegetable gardens. Harnessing these predators; predatory insects, spiders, and birds is but one of the many advantages of having these ‘edge’ plantings.

On a larger scale—say in a park, on a golf course, or on the margins of a fruit orchard, tree nursery, or solar farm—this type of planting also gives operations and maintenance crews many options for management and provides the same benefits of diversity, attraction of pollinators, birds, predatory beneficial insects, and can augment grazing opportunities for sheep, goats, and poultry. Not only do these O/M options reduce overhead costs, but they also present the potential for new revenue streams, as well as increase the public’s enjoyment and acceptance of sites like solar farms and other infrastructure.

This is but one example of how utilizing the 6-3-4™ to guide our horticultural design is scalable from the home landscape to the municipal or commercial scale. In future articles, I’ll address urban site remediation, phytoremediation of soils in the home garden, and particular possibilities for future research and case studies in urban, suburban, and sports facility “engineered” soils.